The doubts on the master of doubt

Larvatus prodeo, ”I advance masked,” wrote Descartes in one of his first letters to a friend, suggesting that he moved upon the stage of the world like an actor. Descartes has somehow always advanced masked, and long after his death. When he left his earthly life in Stockholm on February 11, 165O, due to lung disease or poisoning (the case is still not resolved), the Sun King immediately demanded the return of his remains. It took 16 years before Ambassador Hugues de Terlon, who also had a great penchant for relics and who took the opportunity to keep a finger as a reward for his efforts, transported the body to France in an 80 cm coffin, since he also liked to « travel light ». As the church, which had condemned the philosopher’s writings, refused the funeral, the body was buried almost secretly in the Sainte-Geneviève church in Paris. In 1819, on the occasion of a new burial in the Church of Saint-Germain-des-Près, they discover that the skull had disappeared.

Supposedly, it circulated from one private collection to another. It rises at the surface in the Lund History Museum in the late 1700’s. But in 1821, another skull appears in a casino in Stockholm, which supposedly also belongs to Descartes. The owner immediately sells it to the chemist Jacob Berzelius, who passes it on to Georges Cuvier’s, permanent secretary of the Academy of Sciences. He makes several cross-anatomical comparisons with portraits of Descartes, to finally conclude that this is the ”real” skull of Descartes. On top of that, each owner had their name inscribed on the skull, as if these proud thieves wanted to inscribe their name in history. Today, the skull of Descartes, the real one? the fake? who knows? is found at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, next to a monkey. Other skulls have since appeared and the authenticity of the relic has continued to be questioned. The fact that the master of doubt now makes us doubt the authenticity of his skull, would undoubtedly have amused him a lot.

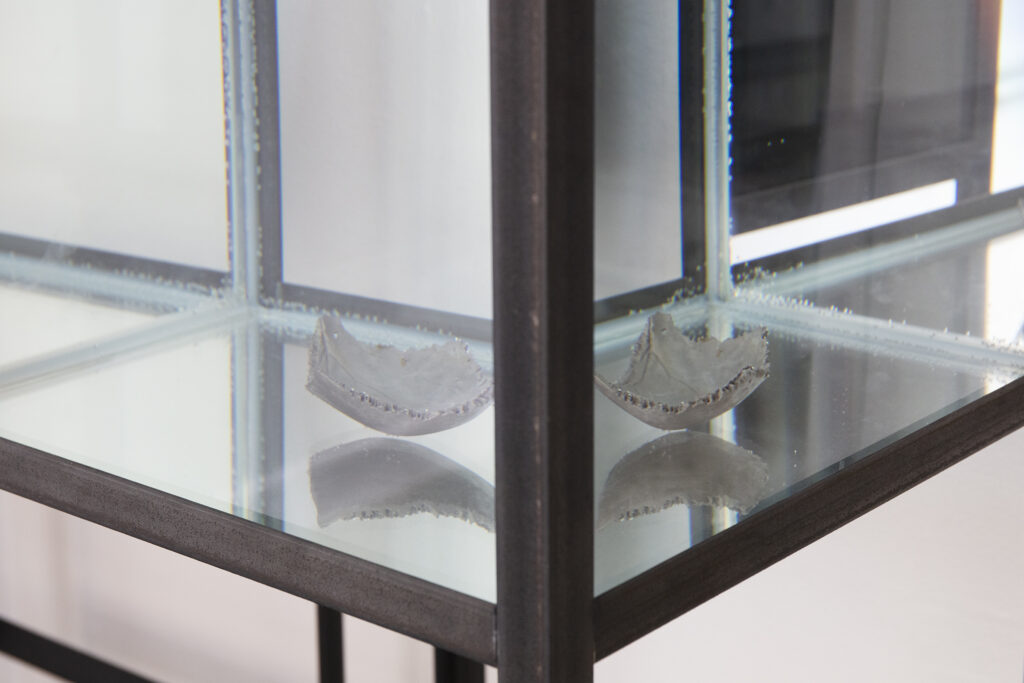

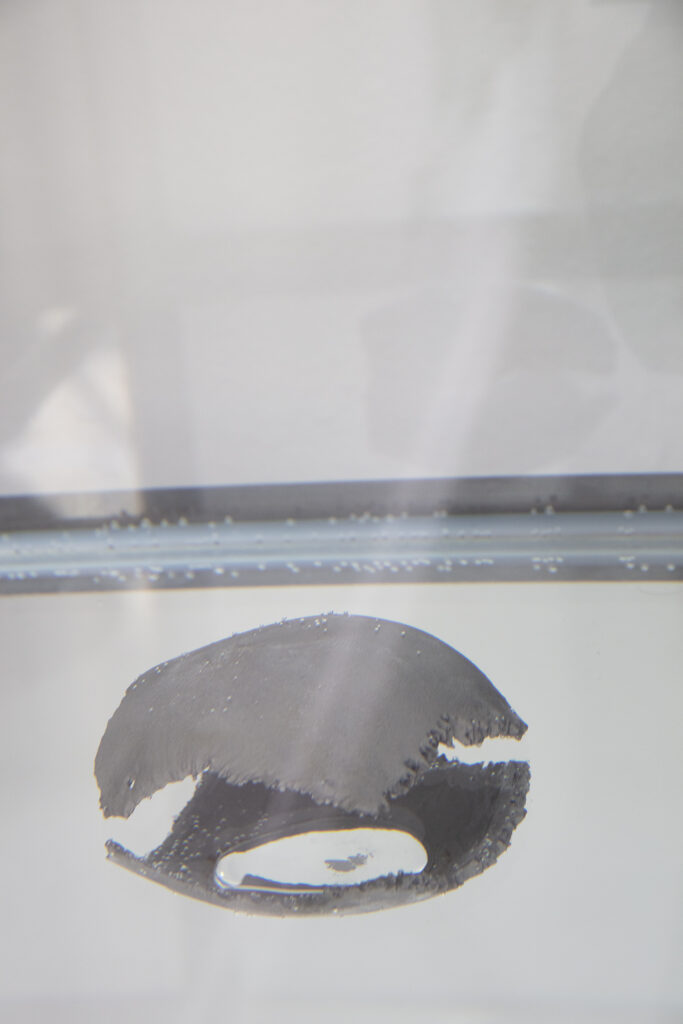

Joakim Forsgren, who has always played with systems of belief and of doubt, has devoted an entire exhibition to the multiple appearances of Descartes’ skulls in Sweden, which were 3D printed from a CT scan made with the supervision of the artist at Lund Hospital. He also collected all the stories that arose around the famous skull, which he introduced into the work to intensify its aura. Hamlet’s famous meditation to be or not to be on Yorick’s skull is thus transformed through Forsgren’s work into believing or not believing in the authenticity of Descartes’ skull, but also into a meditation on the vanity of desire to know at all costs whether the skull belonged to Descartes or not.

As we know, Descartes constantly doubted the full use of his senses and wondered if a God or an evil genius was deceiving him. To get out of the prison of doubt, he invents a reasoning that bites his own tail: if the almighty God who deceives him is bad, then he would be much smaller than a good God, for good is infinitely greater than the evil. Descartes thus comes to the conclusion that God cannot let him be wrong in the long run. God takes him out of his doubts and paradoxically appears in his rationalist philosophy as a Deus Ex Machina who puts everything in order again.

Who is the artist’s God? The gallery owner? The curator? The art theoretician? The critic? Isn’t art a permanent questioning of authorities, an exercise in freedom, as well as an interaction with everything that stands in the way of our understanding? A permanent doubt which, unlike Descartes – the learned man – does not attempt to reach absolute truths? In Forsgren’s meditation chamber, around Descartes’ skull, we find a number of objects that question scientific knowledge, in a sort of inverted laboratory that encourage us to accept our doubts and our anxieties regarding our ignorance, and to dare to pursue Descartes’ initial thought to the end.

Sinziana Ravini

Tvivlet på tvivlets mästare

Larvatus prodeo, « jag avancerar maskerad », skrev Descartes i en av sina tidiga brevkorrespondenser. Descartes fortsätter än idag avancera maskerad och på sätt han hade nog inte ens vågat drömma om. När han den 11 februari 165O lämnade jordelivet i Stockholm, till följd av lungsjukdom eller förgiftning, begärde Solkungen genast återlämnandet av hans kvarlevor. Det kom att dröja 16 år innan ambassadören Hugues de Terlon, som för övrigt hade stor fäbless för reliker och därför passade på att behålla Descartes långfinger, transporterade kroppen till Frankrike i en kista på 80 cm, för Terlon älskade också att resa lätt. Men då den franska kyrkan som hade fördömt filosofens skrifter vägrade en begravning med pompa och ståt, begravdes kroppen nästan i smyg i Sainte-Genevièvekyrkan i Paris. När man 1819 vill överföra kvarlevorna till den mer anrika Saint-Germain-des-Prés, upptäckte man att skallen var borta.

Den kuskades runt mellan olika ägare för att så småningom hamna på Historiska Museet i Lund. 1821 dyker det upp ett till kranium på ett Casino i Gamla Stan som också påstås tillhöra Descartes. Ägaren sålde den genast vidare till kemisten Jacob Berzelius som gav den vidare till fransmannen Georges Cuvier, vetenskapsakademins ständige sekreterare som gjorde flera tväranatomiska jämförelser med porträtt av Descartes, för att slutligen komma fram till att detta var Descartes riktiga skalle! Varje ägare hade skrivit sitt namn på skallen, som om dessa stolta tjuvar ville skriva sig in i historien, signera ett verk som tillhörde dem. Nu tronar kraniet på Musée de l’Homme i Paris, intill en apa. Fler skallar har dykt upp sen dess och relikens äkthet har fortsatt att ifrågasättas. Att tvivlets mästare får nu oss att tvivla på hans skalles äkthet hade säkert fallit honom på läppen.

Joakim Forsgren som alltid lekt med tron och tvivlets tankeströmmar ägnar nu en hel utställning åt den svenska upplagan av Descartes multipla skallar, som 3D-printats från originalscanning i en datortomograf under hans överseende på Skånes Universitetssjukhus i Lund. Han är också intresserad av alla historier som uppkommit kring den beryktade skallen och storytellingens betydelse för ett objekts aura. Hamlets att-vara-eller-icke-vara-meditation över Yoricks kranium förvandlas således i Forsgrens tappning till att-tro-eller-icke-tro på äktheten av Descartes dödskalle, men också till ett nutida vanitasmotiv som reflekterar över fåfängligheten i att till varje pris vilja veta vems hjärna detta kranium härbergerat.

Descartes tvivlade som bekant på sina sinnens fulla bruk och oroade sig för huruvida en ond demon lurade honom. För att ta sig ur tvivlets gissel skapade han ett resonemang som bet sig själv i svansen: om den allsmäktige Guden som lurar honom var ond, så var han i så fall betydligt mer underlägsen en Gud som är god, ty godheten är oändligt mycket större än ondskan. Descartes kommer alltså fram till att den gode guden kan inte låta en människa lura sig själv i det långa loppet och tar sig ut ur tvivlet via Gud som dyker upp i hans rationalistiska filosofi likt ett Deus Ex Machina som ställer allting till rätta igen.

Vem kan konstnären vända sig till i sitt sökande efter mening? Gallerister? Curatorer? Lärare? Kritiker? Stipendiegivare? Är inte konstskapandet ett idel tvivlande befriat på allt vad Gudar och yttre instanser heter? En övning i frihet? Ett umgänge med det som motstår vår förståelse? En uppmaning till ren och skär ödmjukhet? Med andra ord rena raka motsatsen till vad Descartes inkarnerade – l’homme savant. I Forsgrens meditativa kammare som omgett Descartes skalle med en rad ting, vätskor och fotografier som likt ett inverterat laboratorium representerar olika slags tankehinder och distanseringar kan vi öva oss i att acceptera både okunskapens och tvivlets agonier, med andra ord – våga tänka Descartes initiala tanke hela vägen ut.

Sinziana Ravini